Modeling

Los Angeles faces a future with less imported water. Infrastructure and institutions will have to adapt. Understanding emerging policy and investment needs requires analysis across systems, a typically elusive goal within the diverse and disparately managed water systems of L.A. A more comprehensive analysis of water resources in Los Angeles requires an understanding of people, pipes, and plants. It could also be flexible to incorporate the fast-changing landscape of models, data, and analysis that the active agencies of the region continue to develop.

The Artes Project

We developed a water supply model for the metropolitan L.A. County region (Artes) to understand the potential for enhancing local water use across scenarios of demand and supply. The basic approach combines knowledge from engineering, hydrology, ecology, and sociology. The model is intentionally lightweight. Flexible and adaptive modeling can address many questions at multiple geographic scales, while also being able to incorporate new tools, data, and other models that are released. This model was developed to:

- Determine how local groundwater, recycling and stormwater capture supplies could maximally meet water demands across L.A. County, based on current knowledge of hydrology and hydrogeology

- Analyze tradeoffs in per capita water demand and available imported water supplies

- Investigate system-wide effects of increased conservation

- Minimize assumptions regarding data gaps

- Use modeling to highlight to key gaps in scientific understanding, while creatively addressing the shortfalls in a precautionary manner. For instance, we compare modeled and historic groundwater pumping and managed aquifer recharge to assess the potential for groundwater overdraft.

Contributors

The project compiles and integrates results from years of research at UCLA and elsewhere. Erik Porse is the principal architect of Artes and Stephanie Pincetl is the principal investigator. Mark Gold and Katie Mika at UCLA worked to collect data, calibrate methods, and interpret results based on complementary studies of OneWater policies in the City of Los Angeles, funded by the LA Bureau of Sanitation. That research, being released in 2017, is examining local water supply potential for each watershed in the City of LA, along with economic and energy implications of future supply regimes. Diane Pataki and Liza Litvak at the University of Utah developed assessments of urban tree canopy water needs based on experimental data. Terri Hogue and Kim Manago at the Colorado School of Mines supported data collection, analysis, and calibration across the myriad models for LA water management. Madelyn Glickfeld and Kartiki Naik (now at the California State Water Resources Control Board) at UCLA reported results of L.A. agency water losses used in modeling. Former CCSC researchers Debbie Cheng, Paul Cleland, and Janet Rodriguez all contributed to the sizable task of collecting and collating data. Artes contributes to UCLA's Sustainable LA Grand Challege goal of achieving 100% local water supply in Los Angeles.

The project has been supported by the National Science Foundation's Water Sustainability, and Climate program (NSF-WSC #1204235), the Haynes Foundation, and the L.A. Bureau of Sanitation.

Numerous area agencies generously provided data, including the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, the Los Angeles Bureau of Sanitation, the L.A. County Department of Sanitation, Burbank Water & Power, the Water Replenishment District of Southern California, and the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power. Special thanks to Lee Alexanderson and Daniel Bradbury at the L.A. County Department of Public Works for assistance in interpreting WMMS outputs.

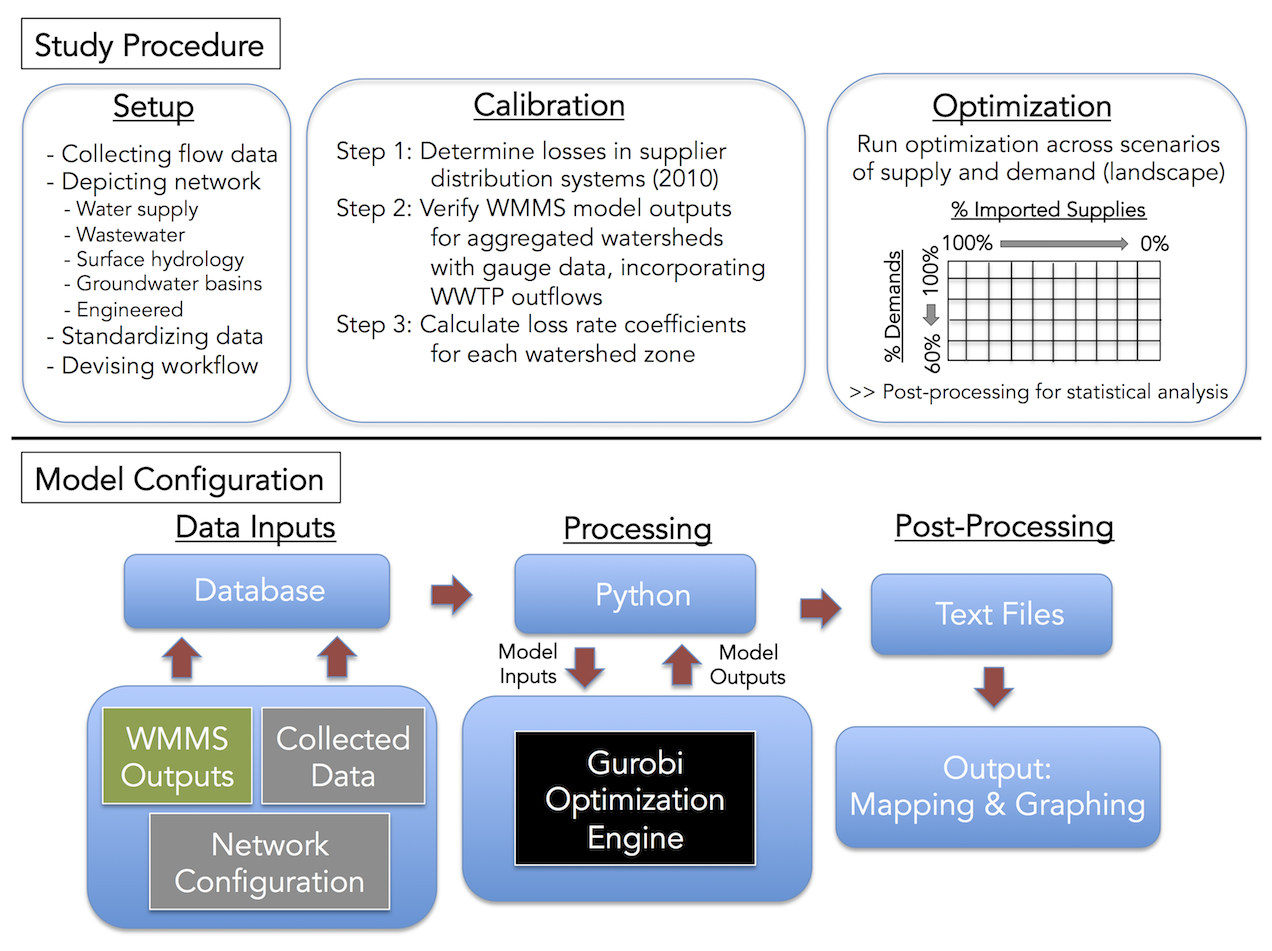

Architecture

The software is open-source and uses Python along with an optimization engine (Gurobi) to run network flow decisions. Source code and data is available in a Github repository. The network structure allows for incorporating future models and new data that arise.

The model uses either global or annual optimization (perfect foresight or annual foresight). The objective of reported results so far balances two goals of maximizing water flows from local sources with minimizing shortages among water retailers. It is a monthly model that quantifies water flows over a 25-year record (1986-2010) for which sufficient historic data is available across systems. Model objectives, time frames, and geographic scope are scalable and adaptable. Studies underway will contribute results of different objective functions that can illuminate predictive understandings for planning.

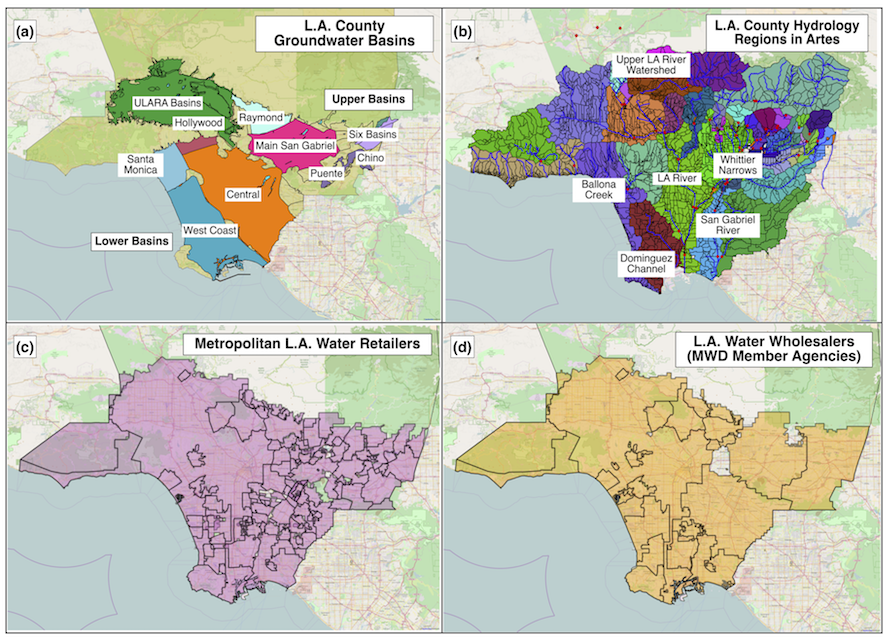

Artes uses a link-node network structure to represent the connected institutional, engineering, hydrologic, and hydrogeologic features. Surface water hydrology is simulated by the Water Management Modeling System (WMMS) from the County of Los Angeles, which models surface water flows in the unaltered network. Flows in the altered network in L.A., which includes city and county water supply and drainage infrastructure such as wastewater treatment plant outflows, contributes significantly to seasonal water balances in the semi-arid region and represented in the nodes. In Artes, these are represented by nodes that are connected to surface and groundwater features based on existing physical infrastructure. The institutional management hierarchy in Artes includes features with associated groundwater pumping rights, imported water allocations, and water recycling arrangements. Historic hydrology and imported water values are inputs for the optimization.

Documentation

Details of model structure, development, and summary findings are documented in research papers. Source code is available in a Github repository and commented as best as possible (though likely inadequately) for any future users. A documentation report and user guide is also available in the repository. Some sources are listed below.

- Porse, Erik C., Kathryn B. Mika, Elizabeth Litvak, Kim Manago, Kartiki Naik, Madelyn Glickfeld, Terri Hogue, Mark Gold, Diane Pataki, and Stephanie Pincetl. (2017). “Systems Analysis and Optimization of Local Water Supplies in Los Angeles.” Journal of Water Resources Planning and Management.143(9). September 2017.

- Pincetl, Stephanie, Erik C. Porse, and Deborah Cheng (2016). “Fragmented Flows: Water Supply in Los Angeles County”. Environmental Management. 58(2). Pg. 208-222.

- Porse, Erik C., Madelyn Glickfeld, Keith Mertan, and Stephanie Pincetl. (2015) “Pumping for the Masses: Evolution of Groundwater Rights in Metropolitan Los Angeles.” Geojournal. DOI: 10.1007/s10708-015-9664-0.

- Litvak, E., McCarthy, H. R., and Pataki, D. (2017). “A method for estimating transpiration from irrigated urban trees in California.” Landscape and Urban Planning.

- Litvak, E., K. Manago, T. S. Hogue, D. E. Pataki (2017). Evapotranspiration of urban landscapes in Los Angeles, California at the municipal scale. Water Resources Research 53 (2017) DOI: 10.1002/2016WR020254

- Litvak, E., Mccarthy, H. R., and Pataki, D. E. (2011). “Water relations of coast redwood planted in the semi-arid climate of southern California: Water relations of urban redwood.” Plant, Cell & Environment, 34(8), 1384–1400.

- Litvak, E., McCarthy, H. R., and Pataki, D. E. (2012). “Transpiration sensitivity of urban trees in a semi-arid climate is constrained by xylem vulnerability to cavitation.” Tree Physiology, 32(4), 373–388.

- Litvak, E., and Pataki, D. (2016). “Evapotranspiration of urban lawns in a semi-arid environment: an in situ evaluation of microclimatic conditions and watering recommendations.” Journal of Arid Environments, 134, 87–96.

- Pataki, D. E., McCarthy, H. R., Litvak, E., and Pincetl, S. (2011). “Transpiration of urban forests in the Los Angeles metropolitan area.” Ecological Applications, 21(3), 661–677.

- Manago, Kimberly F. and Terri S. Hogue, 2017. Urban Streamflow Response to Imported Water and Water Conservation Policies in Los Angeles, California. Journal of the American Water Resources Association (JAWRA) 1–15. DOI: 10.1111/1752-1688.12515

- Gold, M., Federico, F., and Pincetl, S. (2015). 2015 Environmental Report Card for Los Angeles County. UCLA Institute of the Environment and Sustainability, Los Angeles, CA.

- Stephanie Pincetl, Madelyn Glickfeld, Deborah Cheng, Miriam Cope, Kartiki Naik, and Erik Porse, Kristen Holdworth, and Celine Kuklowski (2015). Water Management in Los Angeles County; a Research Report. Presented to the John Randolph Haynes and Dora Haynes Foundation. UCLA Institute of the Environment and Sustainability.

- Naik K, Glickfeld M (2015) Water Distribution System Efficiency: An Essential or Neglected Part of the Water Conservation Strategy for Los Angeles County Water Retailers? UCLA Institute of the Environment and Sustainability, Los Angeles, CA

FAQs and Notables

Q: What does Artes stand for?

A: It is short for artesian well, which is an original source of local water for Los Angeles... and modeling can be as much art as science.

Q: What is the geographic scale of Artes?

A: The model includes the metropolitan regions of L.A. County in the coastal and upper basins.

Q: What is the temporal resolution in Artes?

A: It is a monthly model.

Q: Can I get access to the model?

A: Yes, the code is open-source and the data and documentation is in a Github repository. Running the model with the current solver, though, does require a license on a local machine.

Q: Is it event-based or continuous?

A: It is a continuous model across 25 years.

Q: Are there limitations to this approach?

A: This could result in overestimates of stormwater capture in basins when modeled volumes of hydrologic events occur in a time frame too short for routing to capture basins. A similar situation could occur with treatment plant inflows. Caveats and thoughtful interpretation are necessary in using these outputs directly.

Q: Are there other limitations to the model?

A: Yes, of course, like all models. A big limitation is a lack of scientific knowledge and data regarding surface-to-groundwater interactions, which drives distributed recharge. Loss rates are another source of uncertainty. Limitations are detailed in our methods paper.

Q: The results imply more stormwater capture than historic numbers. Is this realistic?

A: Results are optimized. The model only includes recharge capacity from centralized managed aquifer recharge, but it could overestimate recharge due to the extreme hydrology of many L.A. rainfall events or the need to bypass the "first flush" of runoff for water quality. The WMMS model results capture this more eloquently. But results from Artes are usefully interpreted as the volume of managed aquifer recharge necessary in both centralized and distributed facilities that is known to reach drinking water aquifers.

Q: The known capacity of groundwater basins in L.A. is big. Couldn't we just use that groundwater?

A: Yes. As evidenced during the current drought, mining deeper groundwater always arises as a water supply option. Tradeoffs for using more groundwater in L.A. include pumping costs for deeper or new wells, as well as the uncertainties in managing contaminated groundwater aquifers.

Q: Does Artes do water quality?

A: It does not explicitly report water quality results. WMMS reports water quality values and can be employed to output water quality.

Q: Can Artes help answer the question of ___________ in L.A. water management?

A: Yes, probably, with a bit of tweaking.

Q: It seems like the model would be better if ___________ were included. Is that possible?

A: Yes, it's possible and we probably agree. Get in contact with suggestions at: eporse (at) ioes.ucla.edu.

Q: What about energy and economic considerations?

A: Stay tuned. Neither Rome nor Los Angeles was built in a day.